This week, the Interactive Advertising Bureau released the third iteration of our ground-breaking study, “The Economic Value of the Advertising-Supported Internet Ecosystem.” The research, undertaken since 2009 by a team led by John Deighton, the Baker Foundation Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School and an authority on consumer behavior and marketing, found that digital advertising propelled $1.1 trillion into the U.S. economy in 2016— more than double the contribution it made in 2012, the last time Prof. Deighton explored the territory. The ad-supported internet ecosystem today accounts for 6 percent of the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP), representing a 20 percent compound annual growth rate from 2012 to 2016—five times the average American GDP growth during the same period. More than 10 million jobs, in every Congressional district in the country, owe their existence, directly or indirectly, to Internet advertising.

But that phrase “directly or indirectly” seems to stick in some critics’ craws. Fast Company magazine called the very concept of an ad-supported Internet a “fallacy.” The study “counts in its top-line totals revenue and jobs from businesses that rely on the internet but don’t use an ad revenue model,” reporter Mark Sullivan complained. The Wall Street Journal joined in the criticism. “The IAB is using a rather broad definition of what an internet business is, counting fully ad supported businesses such as BuzzFeed and Google as well as apps such as Uber,” the newspaper grumbled. Jason Kint, CEO of Digital Content Next, objected: “A Harvard study literally categorizes the entire internet as ‘ad-supported.’ That’s the most ridiculous overreach I’ve seen in a decade.”

But that phrase “directly or indirectly” seems to stick in some critics’ craws. Fast Company magazine called the very concept of an ad-supported Internet a “fallacy.” The study “counts in its top-line totals revenue and jobs from businesses that rely on the internet but don’t use an ad revenue model,” reporter Mark Sullivan complained. The Wall Street Journal joined in the criticism. “The IAB is using a rather broad definition of what an internet business is, counting fully ad supported businesses such as BuzzFeed and Google as well as apps such as Uber,” the newspaper grumbled. Jason Kint, CEO of Digital Content Next, objected: “A Harvard study literally categorizes the entire internet as ‘ad-supported.’ That’s the most ridiculous overreach I’ve seen in a decade.”

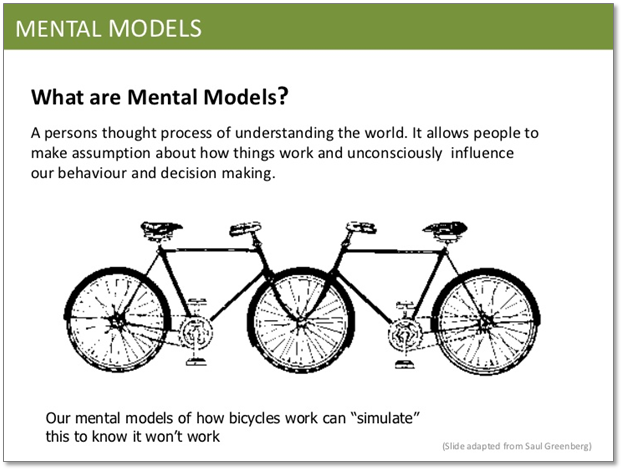

I think these journalists and trade group executives are hostage to an obsolete mental model – a paradigm that’s unfortunately still widely held, and could be a significant obstacle for publishers, agencies, and brands alike.

Boxes and Slots

The concept of “mental models” was developed in the late 19th Century by the philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce, who was also responsible for developing the field of inquiry known as semiotics, the theory of signs. A mental model, Peirce said, is a form of human reasoning, a psychological representation of situations people could encounter or could imagine encountering. Peirce and his successors in the fields of psychology, philosophy, and cognition showed that these images of reality underlie our ability to anticipate and explain the world around us.

Walter Lippmann’s groundbreaking 1921 book Public Opinion – the foundational document for modern journalism, public relations, and advertising – employed the concept of mental models to explain how these disciplines helped people adjudicate between “the world outside and the pictures in our heads,” ideally for the advance of liberal democratic societies and open economies. Thomas S. Kuhn, whose concept of paradigms and paradigm shifts in scientific communities transformed our understanding of the history of science, also owed more than a passing debt to Peirce.

The word “advertising” calls up a mental model, and if you’re over the age of 30, it’s a fair bet that you share it with everyone in your demographic cohort. “Advertising” conjures forms of marketing communication that sit inside boxes on a page or screen, or time slots within motion picture narratives – ads and commercials, or, in the argot of media and marketing, spots and dots.

The word “advertising” calls up a mental model, and if you’re over the age of 30, it’s a fair bet that you share it with everyone in your demographic cohort. “Advertising” conjures forms of marketing communication that sit inside boxes on a page or screen, or time slots within motion picture narratives – ads and commercials, or, in the argot of media and marketing, spots and dots.

But that’s not what advertising is – not any more, and perhaps not really ever.

As long ago as the early 1980s, it was a commonplace that over a 20-year period, advertising spending had done a complete reversal, with some two-thirds of marketing investments having shifted from “above-the-line” media formats (that is, radio and TV spots, magazine and newspaper ads, and the like) to “below-the-line” disciplines, such as consumer promotions, trade promotions, public relations, and direct-response marketing. In other words, even then, advertising wasn’t all – or even mostly – “advertising.”

But was it ever? A tour through history shows that advertising used to be far more varied than prisoners of the mental model understand. In 1933, Procter & Gamble began directly producing, through its advertising agencies, the soap operas that framed its ads for Oxydol detergent. (One of Procter’s agencies, D’Arcy Masius Benton & Bowles, still had a soap opera production facility in the basement of its midtown New York headquarters when I was covering the advertising business for The New York Times in the late 1980s.) Indeed, what we today call “branded content” infused early radio; the Young & Rubicam agency itself hired an unknown comic named Jack Benny and authored his famous on-air greeting, “Jell-o again!”, on behalf its client General Foods.

Another 21st Century digital construct – “native advertising” – was festooned across the first three seasons of “I Love Lucy” on CBS in the 1950s, with stars Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball, in cartoon form, and live, in character as the Cuban bandleader and his lovably ditzy wife, touting the cigarettes of their sole sponsor, Philip Morris.

The phenomenon of content marketing wasn’t limited to broadcasting. GQ magazine was launched in 1931 as Apparel Arts, a men’s fashion catalogue and retail trade publication. To this day, fashion magazines happily and publicly skirt the boundary between editorial and advertising content, especially in print and digital photo spreads. It’s a central component of their value proposition, to consumers and advertisers alike.

Arguably, the narrowing of advertising into the mental model “advertising” only really took hold in the late 1950s, with the industrialization of marketing communications that coincided with the growth of television. As head of NBC from 1949 to 1955, Sylvester “Pat” Weaver (a former president of Young & Rubicam) developed what became known as the “magazine model” of television advertising, by which multiple advertisers, rather than a single marketer, sponsored a show.

This innovation – which was boosted by the “quiz show scandals” of the era, which showcased to regulators and the public the uncomfortably direct power advertisers had over program content – dramatically increased advertising volume and advertiser visibility, even as it diminished their influence over content. Network profits soared, and the multiple-advertiser model remains the standard for TV advertising to this day. (From the quiz show scandals also emerged the Media Rating Council, the ad industry’s standard-bearer for media measurement.)

Industrial Advertising Paradigm

That industrial model of “advertising” transferred itself to the Internet. What is “programmatic advertising,” after all, if not the mass-produced, mass-distributed spots and dots transferred from the era of mass media to the era of the Internet? But just as the real and diverse history of advertising belies the mental model that imprisons us, so too does the current reality of digital advertising defy that old mental model.

It’s not just that older concepts like soap operas and talent-voiced ads have found renewed life in the form of branded content and native advertising. Of more import, the lines that used to cleanly separate a product or a service from its advertising and from its retailing are themselves blurring.

I heard this firsthand last month at IAB@MWC, the annual thought leadership conference we convene at the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona, Spain. Leonid Sudakov spoke in great detail about his transition from the position of Chief Marketing Officer of Mars Petcare, overseeing advertising and communications for a portfolio of billion-dollar brands, to a new position as the company’s Global President for Connected Solutions. He and the company had recognized that mobile applications and data could not only make their marketing communications more attributable and effective – they could inform, infuse, and even constitute new products and services. Some of those products and services Mars Petcare could give away to its consumers, to create or reinforce a relationship that would enable the sale of more pet food. But some of those new products and services could be sold independently, even becoming whole new lines of business.

Among those new mobile innovations: Whistle, a “Fitbit for dogs” app it acquired last year that helps pet owners keep track of their pets’ workouts.

Among those new mobile innovations: Whistle, a “Fitbit for dogs” app it acquired last year that helps pet owners keep track of their pets’ workouts.

Is Whistle a service? A loyalty program? An ad? Content? A game? A marketplace? The answer: It’s all of the above.

I heard similarly from a raft of marketers, across a diversity of categories, who graced our stage in Barcelona. Lufthansa, Red Bull, and Procter & Gamble were among the brands that described the transformation of their marketing functions into innovation and R&D hubs.

Which brings me back to the complaint that the IAB/Harvard economic value study uses an “overly broad” definition of advertising, even including in its calculation of jobs growth and economic contribution companies like Uber, which “don’t use an ad revenue model.”

In Washington, D.C. yesterday, I had the pleasure of unveiling “The Economic Value of the Advertising-Supported Internet Ecosystem” with Prof. Deighton to a packed audience in an office at the U.S. Capitol. In the Q&A session afterward, I asked the Harvard Business School Professor about this critique. How could he justify including companies like Uber and Netflix in his analysis, I queried?

“We are incorporating and trying to encompass all forms of commercial and market communication, even as they change into forms not previously known,” Prof. Deighton said. An app, he offered, is simply a modern form of communication that calls attention to a product; the fact that it may also be part of the product itself is both material and irrelevant. “In times past, if you wanted a car service, you had to look in the Yellow Pages,” he said. “The Uber app is a replacement for that, at the same time it is the underpinning of the company’s service.”

“Make the Markets”

Or, as Prof. Deighton, who has built courses and an entire inquiry stream at Harvard on “Big Data in Marketing” based on his team’s seven years of work with the IAB, says more formally in the study itself:

“One question the study seeks to explore is the extent of the ecosystem’s reliance on advertising to support it. Advertising can be read narrowly as payments by advertisers to publishers, following the precedent established in the pre-internet world. In that world ‘advertising’ did not cover advertising on so-called ‘owned’ media such as displays on the sides of a firm’s trucks and buildings, nor did it cover direct mail, catalog retailing, or telemarketing. However, in the digital economy, this distinction underplays one of the important economic consequences of the internet. The marketing effects of the internet ecosystem, particularly those of owned and earned media, are very substantial. Payments to publishers do not measure all that the internet does to make the markets that create the economy.

“The internet, in sum, serves many commercial purposes besides advertising in the narrow sense of the word. Websites can serve as storefronts, point-of-purchase stimuli, as tools for conducting research online for offline purchase, and to transact online based on research offline. Websites can aggregate consumer reviews. Consumers can see products promoted and buy them in a single visit. They can download digital products and consume them online. They can share news about their purchases and opinions and review products and services on social media.”

(Those who can take time away from tweeting should explore Prof. Deighton’s complete description of the study’s methodology.)

So, yes, welcome to the trillion-dollar Internet advertising ecosystem. If present growth trends continue, it will be worth $2 trillion to the U.S. within the next four years. Brands, agencies, publishers, and technology suppliers should embrace its diversity, for that is your opportunity to thrive.

And that’s how the mental model crumbles.